- Born: William Ashby, 2 July 1819 in Bathurst Township, Lanark County, Upper Canada to John Ashby (1769-aft 1843) and Susanna Andrews (1775-bef 1842)

- Married: William Ashby married Elizabeth B. Foster (1823-1902)

- 7 Nov 1843, Bathurst Township, Lanark County, Ontario, Canada

- Died: 21 April 1899, Fallbrook, Bathurst Township, Lanark County, Ontario, Canada

- Buried: Pinehurst Cemetery, Playfairville, Bathurst Township, Lanark County, Ontario, Canada

- Family Tree: William Archibald Ashby in Lanark County Origins

- Relationship to author: maternal great-great Grandfather

- Children: Isabella Ashby (1845-1921), Ruth Ashby (1848-bef 1881), Susan Rene Ashby (1850-1930), Elizabeth Ashby (1851-1920), John Ashby (1854-1926), Harriet Ashby (1858-1935), Martha Ashby (1859-1934), William Samuel Ashby (1862-1913)

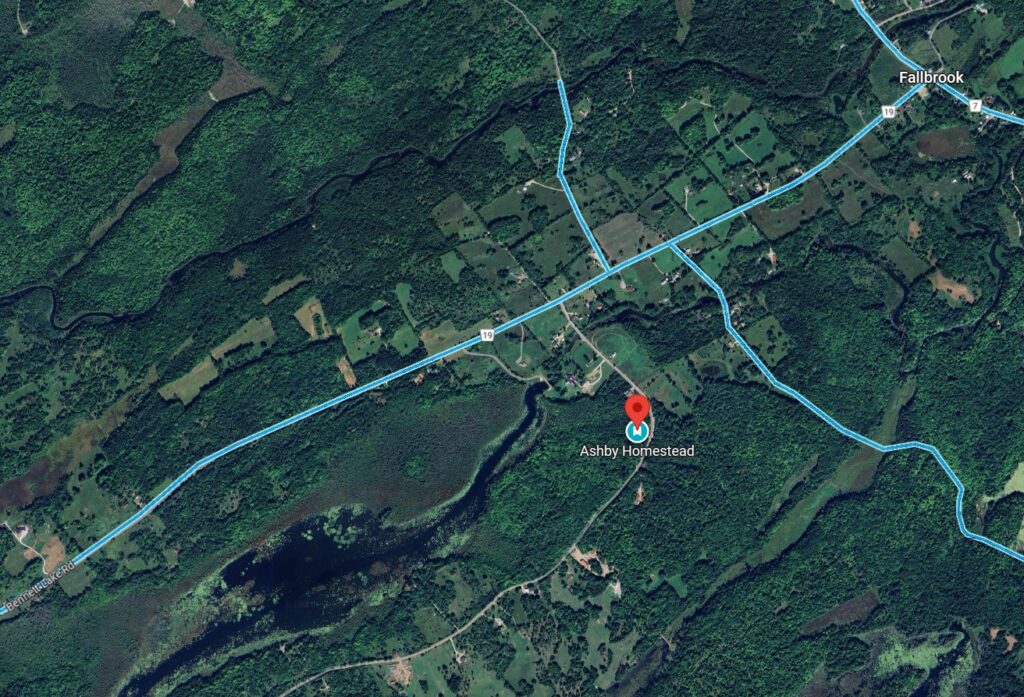

William Archibald Ashby my 2x great grandfather, was born the 2nd of July 1819 in the newly surveyed township of Bathurst, Bathurst District, Upper Canada. He was born shortly after John and Susanna Ashby found a lot that became their lifelong home. Sergeant John Ashby and Susanna both had previous marriages. Between them, there were eight children born. William was the only child to survive to adulthood. He was one of the first children to be born in the community near Fallbrook. William’s family was the second generation to live on lot 17 NE in concession 10, along the 10th line of Bathurst township, close to the future site of Fallbrook village.

William’s Childhood

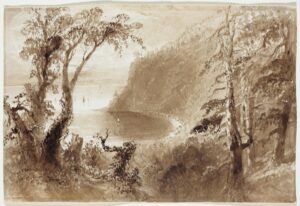

Much of William’s childhood was spent learning the lore of the nearby lake and the surrounding forests. His father, John Ashby, a former sergeant in the British army, served at the garrison at Quebec, Lower Canada before settlement. After spending more than a decade in the Canadian wilderness, John was knowledgeable about life in the Canadian frontier. Susanna, William’s mother also spent several years living at the garrison and had learned many survival skills. As William grew he learn to understand the about the challenges and the skills needed for life in the wilderness. The indigenous people, the Algonquins, who lived and hunted through this area were known to be helpful to the settlers, teaching adaptive skills. New settlers brought with them, skills needed to build and operate mills and resources required to establish businesses. The new businesses created opportunities for employment. The timber industry employed many and provided the opportunity to obtain money for investment in additional or new land. As a result, changes in the backwoods of Lanark county during William’s lifetime, took him from the settlement period, through the lumbering era, into a time of roads, businesses, villages, and opportunities.

Involvement in the Timber Industry

No doubt, during his teen years and early adulthood, William worked during the spring in the timber camps to the north and west of his home. The Gillies, Caldwell or Gilmour camps were spread throughout Frontenac, Renfrew and Lanark counties as well as along the Ottawa river. By the 1840s the small independent lumbermen were being supplanted by lumber “barons” – big operators with extensive timber holding and hundreds of lumberjacks in their employ.

He may have worked at or near the McLaren Depot near Snow Road at one time. Another possibility is that William worked on the construction of the dams and timber slides that were constructed along tributaries of the Ottawa during the 1830s. Many of the lumber workers and river drivers from the area travelled as far north as Lake Timiskaming for work. River drivers guided logs through rivers and lakes on their way to the Ottawa river on their way to Montreal and Quebec.There, William would encounter and perhaps help load the logs and squared timber onto ships sailing for Britain and European countries. Exposure to experiences and people from other communities would excite his imagination and guide decisions later in life..

Shared Youth with Charles Mair

But first, lets think about his time as a lumber jack or river runner. I imagine that William experienced some of the excitement described by Charles Mair. Charles was the son of the merchant, James Mair, of Lanark village, a nearby community. He later became a Canadian poet and journalist and an avid opponent of Louis Riel. Charles wrote of the experiences of his youth on same waterways frequented by William, saying:

“I loved the river life, the great pineries in winter where the timber was felled and squared, the ‘drive’ in spring and the ‘rafting-up’ at Arne Prior or elsewhere, the timber being formed into cribs, securely withed and chained, and united into enormous rafts which were floated to Quebec, to berth at Wolfe’s Cove or Cape Rouge or some other shelter. They were there sold to timber dealers, broken up, and shipped to England in large sailing fleets which came for it twice or thrice a year.

The business had its excitements in these swift tributaries. Real peril there was in ‘jams’ at “unslided” chutes, where the timber piled up to a great height, and the lock-sticks had to be cut to set the jam going. This was dangerous volunteer work, and sometimes fatal. . .

To us youths, the river life, the canoeing, the chutes, the running of great rapids like the Carillon and the Long Sault, the latter more dangerous than the Grand Rapids of the Saskatchewan, which I have repeatedly run in a bark canoe, and very much longer; the braving of the fierce storms of Lake St. Peter, where many a ‘gallant raft’ was blown into single sticks, were the most enjoyable things imaginable.”

The Forests of Lanark and Renfrew County

In a paper written by Theresa Peluso “Tree vs Man: A brief history of the Forests in Lanark County, she quotes the Lanark County Community Forest Management Plan for 2011-2030 (Mississippi Valley Conservation Authority) thus:

“Prior to European settlement about 200 years ago, the area now known as Lanark County was covered in forests. There were white and red pines, maple, ash, elm, beech, basswood, black oak, ironwood, birch, hemlock, and cedar. Almost immediately, the settlers started logging, felling the best white and red pine, as well as oak, ash and elm for lumber. Beech and maple, which were then considered worthless, were piled into heaps and burned. In addition, the settlers would set fires to clear land, and squatters would cut and burn timber for potash. Fires were also caused by the debris from logging operations, and by the sparks and coals that flew off the train engines as they rumbled through the countryside. By 1861, Lavant township (in the area now known as Lanark Highlands) ended up with less than 10% forest cover. And this was before the era of chainsaws, logging trucks and bulldozers!

Fortunately, by the early 1900s, this destruction slowed down. The forests that remained were harder to access, and destructive fires, both natural and man-made, were much less frequent. The focus changed from felling and squaring timber for England to sawing and shipping lumber (both hardwood and softwood) to the United States, Instead of just cutting down trees, the loggers spent more time processing the lumber, which created more jobs locally, and, I presume, reduced the rate of tree removal. Furthermore, in 1921 Ontario passed the Reforestation Act, which enabled the provincial government to promote reforestation, development, and management of lands held by the counties. As a result, by 1991, forest cover in Lanark County had increased to 58.1%. This is why most of the forests in this area today are between 80 and 120 years old. Despite the increased mechanization and efficiency of the lumber industry, numerous factors have reduced the demand for lumber, such as the rise in the Canadian dollar, greater global competition, legal issues (the Canada-U.S. softwood lumber dispute), and increasing energy and labour costs.”

Changes in the Community During William’s Lifetime

Service centre for Logging Camps Suppliers

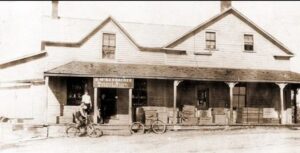

Back at home, the community was changing. New mills were built. Hotels were built to accommodate men who brought grain to the mills to be ground. Fallbrook village became an important wayside for teamsters to rest horses and oxen carrying hay, oats, peas and potatoes to, and timber from, the camps. Food and supplies for the men and their horses or oxen were furnished by the camp operator. Because the camps required large quantities of food, managers preferred to have good land and good farmers near their timber limits. Thus they might buy hay, oats, peas and potatoes more cheaply than they could import from the markets of Lower Canada. What little land near the village of Fallbrook that was tillable, produced crops to be sold. The countryside developed a reputation for producing prime horses and oxen for sale to the camps. Sale of these animals generated income for the ‘locals’ who remained in the community. But the constant flow of strangers through the community brought with it problems. For many years, Fallbrook had a reputation as a village to avoid if one could.

This placed the Ashby homestead and the Bolton mill adjacent to a major “timber highway”. IIn winter the sleighs could cross the ice of the creek. Because Fallbrook was located on a busy route between Perth and the lumber camps two hotels were added to house teamsters passing through and farmers visiting the mills. At first a simple bridge crossed Bolton Creek at the foot of Bennett’s Lake near the corner of the Ashby property and was used by people located north of the lake as was a winter ice road for sleighs. Even after a more substantial toll bridge was built through the village of Fallbrook, t he ‘back bridge’ remained the favored route for local people.

The Mills of Fallbrook

In a short time, there were four mills adjacent to the source of waterpower – a shingle and sawmill, a gristmill, and a carding mill and a woolen mill. Walter Cameron is quoted in The Blacksmith of Fallbrook: The Story of Walter Cameron, Audrey Armstrong, 1979

“Bennett lake/Boulton creek are adjacent to the major timber highway of the Mississippi River made famous by exploits of the Caldwell and McLaren timber empires. Although not part of the water course of the major timber drives, locating sawmills here provided an outlet for timber lying close to the lake watershed. These mills served local needs and products were shipped south to Perth and beyond. There were four mills built along this section of Bolton Creek, thanks to the skill of Alexander Wallace, the local mill wright. Walter Cameron, in 1979 is quoted as saying, that “Now a cow could drink the bit of water that flows through it (Boulton Creek)”. Pg. 17

The Fallbrook mills were important to the local economy. The Bolton family purchased land from John Ashby, William’s father, for the first mill. The Boltons, United Empire Loyalist, moved to Fallbrook in the mid-1820’s to establish mills and helped to establish the community now known as Fallbrook. By the mid 1840’s the family spread to other areas and their property was purchased and operated by others. A few family members married in the community and remained nearby.

By 1851, waterpower no longer met the needs of the local mills. The census reports that:

“Alex Bain is the proprietor of a Grist Mill, which cost L300. Of waterpower, which only gave him a profit of L25. Employed 2. After paying all expenses. He is also owner of a Sawmill which cost L150. Of waterpower which produced two hundred thousand feet of Board. Employed 2. Owing to the scarcity of water last season, did not do so much as in former years.

“Andrew W. Playfair Junior, is Proprietor of a Sawmill which cost L150. It is of water power and produces about 150 thousand feet of Boards. Employs 2.

Wood for Heating Houses in Perth

On pg. 38 Walter Cameron tells the author that,

“A tremendous lot of wood used to go through here on the way to Perth; everybody in town still used wood for heating their houses and for cooking and baking and I can still remember the days when ther’d be a row of sleigh loads of wood that stretched half-a-mile and on both sides of the street (in Perth). . . One evening we stood on the bank up there and counted thirty -five teams and sleighs going empty past our place on their way home from Perth. . .”

The Village During the 1850s, ’60s, ’70s and 80’s

By the 1860s logging interest move north and west and the mills in Fallbrook were no longer strategically located. Carol Bennett and D.W. McCuaig, in their book In Search of Lanark, note that:

“At one point in history, Fallbrook had two hotels. One of these was built circa 1850 by Sandy Bain who was known locally as ‘the Heillan’ (Highland) man. It was a stopping place for drovers, including those who drew supplies for the McLarens’ lumbering camps. These supplies were bought at Perth and taken to the depot at Snow Road, via Fallbrook and McDonald’s Corners. Today this doesn’t seem like a long route, but long ago the roads were usually in poor shape or non-existent, and the trip necessitated overnight stops for the drovers, to say nothing of rest breaks for the horses. This hotel was in operation until approximately a century ago (1880). A larger hotel was built on the same road in the 1860’s. W. Smith was proprietor, and the local post office originated here.

Walter Cameron, uncle of Walter Cameron, purchased the Farmer’s Hotel when he retired from his role as foreman on the log drives to Quebec. This was before 1878.

As time went on the village included two general stores, a school, post office, blacksmith shop, cheese box and cheese factories, with iron and feldspar mines nearby. In 1881, the Belden atlas records that Fallbrook contained a hotel, store, gristmill, sawmill, shingle mill and two carding mills. The Methodist church at Playfair served many of the local needs.During William’s lifetime he watched Fallbrook become a vibrant village with retail, accommodation and other businesses. He experienced ease of travel on improved roads linking the community to others. He experienced the loss of childhood friends as settler families left to find work and better land. He watched the community grow again as families fleeing the famine in Ireland assumed now vacant properties. As a young man he added additional property to his personal land holdings.

Education for William and His Family

William did not have formal schooling. He may have gained his ‘letters and numbers’ in an abandoned shanty on the banks of the creek, under the tutelage of a former military man, oft to be reported as drunk and violent. The nearest school was located in Lanark Village several miles away. In 1842, a School Report indicated that Bathurst township had 13 school sections and that all had operating schools except school section #12, the Fallbrook school section. The building was described as “built of cedar logs and chinked by splints and plastered”. Each spring it would flood. Seating was a bench along the wall. It was not always habitable and a teacher was available only intermittently for many years. Andrew Shanks, the first official teacher was hired about 1860.

It was not until 1864 that a new school was built on concession 11 lot 21, high on the hill overlooking Bolton creek. The building also served as an early church and Sunday school. In 1899, there were enough students to require adding a room and hiring a second teacher.

William Ashby’s Family

William’s mother, Susanna Andrews, does not appear on the Lower Canada Census of 1842 which included some of settled townships of Lanark county. Sgt. John Ashby is still on the militia role of 1843. No death records have been found but it is probable that they died about this time. William Ashby married Elizabeth Foster, a neighbour on 7 Nov 1843. Elizabeth was the daughter of James Foster and Isabella Elliot who arrived from County Armagh, Northern Ireland and settled on Lot 14 concession 10.

William and Elizabeth raised a family on the Ashby homestead overlooking Bennett lake and the Bolton creek. Their children were Isabella (1845), Ruth (1848), Susan (1850), Eliza (1851), John (1854, my great grandfather), Harriet (1858), Martha (1859) and William Samuel (1862). It is probable that their children received little formal education. However, their life experiences set the stage for later generations to spread across western Canada.

- Isabella Ashby (1845) married William Warrington on 3rd January 1865 but William disappeared a short time after. There were two Warrington sons, James and William. In the 1851 census James is listed as 13 years of age and William is listed as 11 years of age. In the 1861 census James is listed as 20 years of age and William is listed as 19 years. By 1871 Isabella is living with and raising six children with “Wm. James Warrington.” The “Wm.” appears to be added as an afterthought. It has been suggested that James may be the father of Mary Ann Warrington, the eldest child and perhaps of all the children. It appears that, at the time of Isabella and William’s marriage, James may not have lived in the community. Through the 1860s he travelled from one militia group to the next, providing training. The family may not have known where he was. A descendant suggests there was a shot-gun marriage, with the wrong brother. Although researched extensively, no trace of William has be found. One of those mysteries yet to be resolved.

- Ruth Ashby (1848) died during the 1870s.

- Susan Rene Ashby (1850) married Alexander Wm. Campbell and move to the Tilson, Manitoba area.

- Elizabeth Ashby (1851) married John Emanuel Milliken and move to South Sherbrooke township near Maberly, Ontario.

- John Ashby (1854) married Mary Anne Clark (1858) and lived on the homestead, in Bathurst township near Fallbrook. They were my great grandparents.

- Harriet Ashby (1858) married Michael Layden and they moved to the Pipestone area of Manitoba.

- Martha Ashby (1859) did not marry but raised two children who carried the Ashby name. She remained in Fallbrook, Ontario.

- William Samuel Ashby (1862) married Charlotte Morris and remained in the Fallbrook, Ontario area.

The Neighbours

The family names of the early community – Bolton, Ennis, Bain, Shillington, Shank, Jackson, Ennis, Foster, Anderson, Hughes, Elliott, Morris, Buffam, Warrington, Balderson, McGregor, and McDonald are names woven throughout my historical research and family history – many connected to my Ashby ancestors. These people formed a tight-knit community in a land of rocks, trees, and swamps, where dependence on help from a neighbour was crucial to survival. Neighbours shared tools, acted as midwives, provided nursing support, and generally worked and played together.

As settlers moved on, leaving lots vacant, children of families who remained acquired their land. Irish families arrived, took up vacant land, got a start in Upper Canada, but most moved on. Francophones from Quebec arrived seeking a home closer to the camps along the Mississippi and Madawaska rivers and became part of the community. Only a few of the military settlers remained. Those who did were former officers and some became prominent in local politics. Those who chose to live on the local allotments hunted, fished and harvested wild produce to supplement a kitchen garden. Sufficient arable land was cleared to provide horses and cattle with hay.

In 1851, at the time of the census, only the Ashby, Foster, Milligan, Clendenning, Parker, and Legary families were residents of the 10th line who received original patents to their land.

William’s Land Holdings

Changes to the Landscape

Much of the 10th concession of Bathurst was a bush trail. The trees on lots along Bennett’s lake were cut during the early days of lumbering in the area and their replacements were slow to regrow. Today the properties are reforested with clearings mainly around dwellings. Today this is a cottage country and a recreational area. Beyond the first ten lots west of Fallbrook, much of the land towards Maberly was never inhabited.

When I visited the Ashby home as a child in the 1950s, and in photos taken in 1930-40 era, the area was open, with visibility stretching to the homes of neighbours. From the Ashby home you could see to the lake. The lake is now distant from the Ashby homestead. Once Bennett lake was a larger body of water. Today the lake is but an widening of a waterway fed by the Fall river, a small stream that flows from Sharbot Lake through the village of Maberly and fed by numerous springs located in South Sherbrooke township and Frontenac county. In a satellite view of William’s property one can see the old shores of Bennett Lake. The lower end of the lake is now low-lying and swampland. Bolton creek holds but a trickle of water. The Ashby homestead is no longer at the foot of the lake. One has to wonder how much of the lakebed has been filled by sunken logs and the waste from sawmills. For a number of years, water level in the lake was maintained by dams built for the mills. They slowly disappeared, allowing the lake water to run freely towards the Mississippi river and ultimately, the Ottawa river.

Changes in Land Ownership

Most of the military settlers and other early settlers moved on in search of better circumstances. Land was often exchanged for small amounts of money or was abandoned. For a time, lots with access to waterpower were highly sought after. The Fall river and Boulton creek were small streams with water supply that fluctuates greatly with the season. The demand for waterpower soon outstripped the capacity of these streams. Those who stayed took over land that was vacated.

On the 1842 and 1851 census most residents are listed as farmers. They and others in the village provided the mills in the community with labour when needed. During the years of the timber trade most able-bodied men worked in the shanties during the winter and on the spring timber drives. When one looks at the agricultural census for 1851 the small acreage tilled, and small harvests recorded, indicate that it was subsistence lifestyle. Fishing in the nearby lake and game from the woods nearby would provide meat for the families. Foraging for berries and other local produce would be important as gardens and orchards are rarely reported until at least the 1861 census.

The Reality of the Land

The reality of the land is best described by Mr. C. Rankin, commissioned in 1835 to report on the status of settlers and echoed by Senator Haydon as,

“a continuous succession of rocky knolls with scraps or bits, seldom exceeding an acre in extent, of good land between”. Haydon, in his book Pioneer Sketches in the District of Bathurst, 1925, states that this and neighbouring land to the west, “should never have been attempted to be settled.”

Land Acquisition

In 1851, William is recorded as owning 300 acres. Of that he records that 12 acres are improved; six acres are under crop and six acres are in pastured. In addition to the 100 acres, Lot 19, inherited from his father, William purchased Concession 10 Lots 17 and 18, in June of 1851 from Maria Graham, a widowed neighbour. He received the deed to these properties in July of 1859. This completed the 300-acre parcel reported in the 1851 and 1861 census, less the part sold to Samuel Bolton by his father. Family members appear to have lived on this land. He had 2 acres of wheat – 30 bushels, 1 acre of Indian corn – 15 bushels, 1 acre of potatoes – 60 bushels, leaving 2 acres to produce the 6 ton of hay recorded. William records 50 pounds of wool and the household has produced 20 yards of fulled cloth and 40 yards of flannel.

In 1861, William controls 250 acres of land, 15 acres under cultivation but only 8 in crop the previous year. He records 30 acres used for pasture, suggesting a significant increase of livestock and crops for sale over the previous ten years. He now has two acres of orchards or gardens. The farm valuation is $600 with implements valued at $25. His wheat production has tripled (total 95 bushels) and includes both spring and fall wheat on a total of four acres, an increase from two. Two acres are now used to grow peas – 25 bushels 1 acre produces 125 bushels of potatoes. Buckwheat, a soil modifier, is now used in a rotation to improve the soil and he has 1 acre producing 12 bushels of produce. A quarter of an acre is used to grow turnips and it produces 30 bushels. Only six tons of hay is produced. This record suggests that the family diet may be more varied at this point and that there was a surplus to be sold to lumber camps still operating in the vicinity.

Land Dispersal

In 1862, William sold part of lot 19 SW , his father’s crown grant, to John Playfair and another portion to George Playfair in 1869. In 1899 it was willed to his son William S. Ashby and Hugh McDonald. Concession 10 Lot 17 NE and Lot 18 SW were transferred to John Ashby and Hugh McDonald. A portion of Lot 18 SW, north of the Fall river, was left to Isabella Ashby Warrington, a daughter.

William and Elizabeth’s Memorials

William passed away 22 April 1899 in Fallbrook, Lanark County, Ontario, Canada and Elizabeth on the 3 October 1902. A simple announcement recorded his death:

“Died – On Saturday, 11th conc. Bathurst, Mr. Wllm. Ashby aged 84 years. He was an uncle of Mr. Harry Johnston of Lanark. Burial at Playfair cemetery on Monday.

Elizabeth passed away in October 1902.

“Mrs. Wm. Ashby passed away at her residence near Fallbrook on Friday of last week, at the ripe old age of 81 years. Deceased was a native of Ireland, her maiden name being Elizabeth Foster. She came to Canada with her parents, the late Mr. and Mrs. John Foster, when a year old, and has been a continuous resident of Bathurst since that time. About sixty years ago she became the wife of Mr. William Ashby, who predeceased her some three years. Five children survive – John, William, and Martha in Bathurst; Mrs. M. Leyden and Mrs. John Thompson, Reston, Man. The funeral took place on Sunday afternoon to the Fallbrook cemetery, Rev. C.A. Heaven conducting the services. – Lanark Era and Perth Courier

William and Elizabeth are buried in the Pinehurst Cemetery, Playfairville, Lanark County, Ontario.