Mary Ann Clark – My Great Grandmother

Born: 8 Oct 1858 in Brockville, Leeds and Grenville United Counties, Ontario, Canada

Married: John Ashby (1854-1926) on 11 Jul 1883 in Lanark Village, Lanark Twp, Lanark County, Ontario, Canada

Died: 26 Feb 1941, Fallbrook, Bathurst Twp, Lanark County, Ontario, Canada

Buried: Pinehurst Cemetery, Playfairville, Bathurst Twp, Lanark County, Ontario, Canada

Family Tree: Mary Ann Clark 1858-1941

Relationship to author: Maternal Great Grandmother

Mary Ann’s Family – Emigration to Hanover Township in the Lehigh Valley

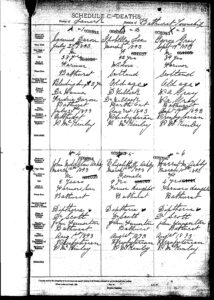

Mary Ann’s parents, James Clark and Mary Ann Gillespie emigrated from Coleraine, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland in 1848 and first settled in Hanover township, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania. They appear in the 1850 census. James Clark, father of James, their daughters Margret and Rachel accompanied them, as did Mary Ann’s father, James Gillespie, and James’ brother Hugh Clark.

Between 1845 and 1855, Pennsylvania, like much of the United States, was in the midst of significant industrial, social, and political change. The state was rapidly industrializing, with railroads and canals expanding trade and transportation, while tensions over slavery and immigration were beginning to reshape political alignments.

Lehigh County, nestled in eastern Pennsylvania, was a microcosm of these larger shifts. The region, historically known for its fertile farmland and strong German cultural heritage, was becoming an industrial powerhouse thanks to one key resource —iron. The Lehigh Valley, with its rich deposits of iron ore and abundant coal from nearby regions, became a hub of the iron industry, particularly after the introduction of anthracite coal-fired furnaces.

Between 1845 and 1855, Lehigh County evolved from an agrarian community into an emerging industrial hub. Iron, railroads, and new waves of immigration reshaped daily life, while national political debates echoed in local taverns and newspapers. The seeds of Pennsylvania’s industrial might and shifting political landscape were firmly planted during this dynamic decade.

Allentown, the county seat, was evolving from a quiet town into a small industrial center. The Allentown Iron Works, established in 1846, helped propel the local economy forward, producing iron for railroads and construction. The Lehigh Valley Railroad was incorporated in 1853, linking Lehigh County to coal mines and larger markets. This drastically improved transportation and commerce, tying the region more closely to Philadelphia and beyond. While iron took the spotlight, the area’s limestone deposits also fueled a growing cement industry, and traditional farming remained strong, with local German-speaking farmers maintaining their influence.

Social & Political Shifts in the Lehigh Valley

The rise of the anti-immigrant ‘Know-Nothing’ movement in the 1850s affected Pennsylvania politics, including Lehigh County, as Irish and German Catholic immigrants faced discrimination. In addition, while Pennsylvania was a free state, debates over the Fugitive Slave Act (1850) and the Underground Railroad intensified. Lehigh County, like much of Pennsylvania, had a mix of opinions, with some aiding runaway enslaved people while others feared political upheaval.

Family Lore from My Grandmother

My grandmother, Isabella Ashby Mather, often told us that her grandmother, Mary Ann Gillespie, owned a general store in Hanover township, suggesting the the Clark family may have brought financial resources with them. However, Mary Ann’s husband, James Clark, suffered health issues resulting from time serving in the military after his arrival. I am so glad that she left notes and relayed tidbits of info about her mother’s family before they came to Canada.

Military Service and the Immigrant Experience

For many new immigrants in Lehigh County and Pennsylvania as a whole, military involvement was often a matter of survival, opportunity, or community obligation. Whether fighting in the Mexican-American War, serving in local militias, defending themselves from nativist attacks, or getting swept up in political violence, many found themselves wielding weapons not long after arriving in America.

The Mexican-American War (1846–1848) was one of the most direct routes for new immigrants into military service during this period. When war broke out in 1846, the U.S. government called for volunteers, and Pennsylvania contributed several regiments. Many immigrants, particularly the Irish and Germans, joined the military as a way to prove their loyalty to the United States, gain steady pay, and potentially earn citizenship more quickly. Pennsylvania raised multiple volunteer units, some of which likely included immigrants from Lehigh County, though most were mustered in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

Pennsylvania maintained an active state militia, and many immigrants, especially German settlers in Lehigh County, were involved in local militia groups. These units functioned as community-based defense forces and were often social as much as they were military. Given Lehigh County’s large Pennsylvania Dutch (German) population, many German immigrants joined or formed militia groups, partially out of tradition and partially to defend their communities from external threats.

During the rise of the Know-Nothing movement, Irish Catholic immigrants sometimes found themselves in violent conflicts with nativist groups, occasionally leading to organized self-defense efforts. The Know-Nothing movement was a powerful nativist political movement in the 1840s and 1850s, built on anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiments. It was officially known as the American Party, but it earned the nickname “Know-Nothing” because its members, when questioned about their activities, would respond, “I know nothing.” Pennsylvania, with its large immigrant population, was a key battleground for the movement. Lehigh County had a strong German-American community, many of its German immigrants were Protestant, making the area somewhat divided in its support for the movement. No doubt this movement worried the protestant Clark family.

With the growth of the iron industry and railroads, labor unrest occasionally flared. Immigrants working in these industries might be recruited into private security forces or even state militias to help suppress worker strikes or riots. The 1850s saw increasing tension between different political factions, particularly regarding slavery and immigration. Militia forces, sometimes including immigrants, were called upon to maintain order during heated elections. While Pennsylvania was a free state, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 meant that federal authorities were actively enforcing the capture of runaway enslaved people. Some immigrants, particularly those sympathetic to abolitionism, were involved in skirmishes against slave catchers.

Immigrants Once Again

In the early 1850s, Mary Ann’s dry goods store burned. This may have represented the loss of all their resources and triggered the need to make a fresh start. Whatever the situation, the family felt unsafe in the local community and decided to move once again, this time to Canada. In the 1911 census her sister’s report that they moved to Canada in 1855, before May Ann’s birth. Mary Ann was born in Brockville, Ontario in 1858. In 1861 the family lived in the west ward of Brockville where her father worked as a laborer. The family belonged to the Free Church (Presbyterian).

It is not known what route they may have travelled from Pennsylvania to Canada but they could have travelled by railroad and steamboat. This trip could be made in 3-5 days, although the easiest was possibly most expensive. The most probable route would include a stagecoach or rail line from Allentown to Easton, PA, where they could connect to the Central Railroad of New Jersey or Delaware & Raritan Canal to reach New York City. They would then transfer to a Hudson River steamboat and travel up the Hudson River to Albany, New York. In Albany they could take a train on the New York Central Railroad to Syracuse and connect to Oswego on Lake Ontario where they would board a steamboat to Kingston or Brockville Ontario. Other less expensive variations of this option included using a route through the Lehigh and Erie canals, again using steamboats and railroads for part of the journey. It is probable that they used one of the less expensive options which might cost from $5-20 per person with additional costs if transporting household goods. Travel by canal and river was seasonal and long journeys came with health risks such as cholera, dysentery and malnutrition.

Arrival in Brockville, Ontario

Brockville was a busy port town on the St. Lawrence river. The harbor was crowded with steamboats, schooners, and barges, moving goods like timber, wheat, and iron between Montreal and Toronto. Warehouses, shipyards, and mills lined the waterfront, where immigrant laborers hauled cargo, stacked lumber, and repaired ships. The air smelled of wood smoke, tar, and river water, and the streets were filled with dockworkers, traders, and farmers bringing goods to market.

Mary Ann’s family settled in the West Ward, a working-class neighborhood where many Scottish, Irish, and German immigrants lived. Housing ranged from small wooden cottages to crowded boarding houses, often shared with other laborers. Many families grew vegetables, raised chickens, or kept a pig to help supplement their food supply. Rent was cheap but wages were low, and the struggle to make ends meet was constant. They may have lived in a boarding house for a short time until family housing could be found but this was expensive. Rental accomodation was sought and found as quickly as possible.

Mary Ann’s father, like many immigrants, likely worked long hours for low pay, taking any job he could find. He might have worked cutting and stacking timber for export in a lumber mill; repairing boats or loading cargo onto steamboats in the shipyards; helping build new houses, roads, and public buildings or working for a local landowner during harvest. Most laborers earned 50 cents to $1 per day, just enough to survive. Work was seasonal, so winter meant unemployment and hardship.

Mary Ann’s mother and older sisters would have taken on household work, sewing, laundry, or domestic service to bring in extra money. Some women worked in textile workshops or helped bake bread for sale. Children helped with chores, gathered firewood, or even found small jobs.

The family attended the Free Church (Presbyterian), a breakaway from the Church of Scotland that emphasized independent worship and strict moral values. The church provided a sense of belonging, social support, and charity for struggling families. Sunday was a day of rest, with families dressing in their best clothes to attend church and share a meal afterward. The church also played a role in education, as many Presbyterians valued literacy. Mary Ann and her sisters may have attended school for a short time. Publicly funded school were being established but attendance was not mandatory. As children of new immigrants, their ability to earn money for the family may have taken precedence over schooling.

By 1871 the family moved to Kitley Twp, near Frankville, ON, and Mary Ann and two younger sisters, Martha and Maria, lived with their parents. Her father, James, was again described as a laborer. In poor health for many years, he died the following year at the age of 49 years.

By 1881, several family members had returned to the family household led by Mary Ann’s mother or, as I suspect, she may have chosen to record the family as a unit although they worked elsewhere. She may have been concerned that they would not be recorded in their ‘servant’ capacity. Margret and Rachel, older sisters, Martha a younger sister and Mary Ann are all listed as ‘servants’ and are believed to have been employed by local families in domestic service. Robert, a brother, was a blacksmith in Fallbrook, a village in Bathurst Twp, Lanark County, Ontario. John, who identified as a laborer, was living in the family home.

Marriage to John Ashby

On July 11, 1883, Mary Ann and John Ashby exchanged vows in a quiet ceremony at the Presbyterian Church manse in Lanark Village, Lanark County, Ontario. Officiated by Rev. James Wilson, their marriage was a new chapter in a story that had likely been unfolding for some time.

How did Mary Ann and John find each other? Family lore offers a charming possibility. With her brother Robert living in Fallbrook, it’s likely that Mary Ann moved there to help with his growing family. It’s said that she worked as a clerk in the McKerracher store, where John was a frequent visitor—perhaps more interested in the warm smile behind the counter than the goods on the shelves!

In 1881, the Belden Atlas painted a vivid picture of Fallbrook, a bustling village brimming with industry. At its heart stood a hotel, a general store, a gristmill, a sawmill, a shingle mill, and two carding mills, all humming with activity. According to the Tay Valley Township website, Fallbrook’s legacy lives on through the stories of its remarkable residents. Among the pioneering families that shaped this industrious community were the Ashbys, Bains, Blairs, Buffans, Ennises, Donaldsons, Foleys, Keays, Playfairs, McKerrachers, Smiths, and Wallaces. Three men, in particular, left an indelible mark on Fallbrook’s history:

- Robert Anderson, an innovative orchardist, introduced the Lanark Greening Apple, a hardy, oversized variety that thrived across Lanark County.

- William Lees Jr. wore many hats—Head of Council, Justice of the Peace, Warden of Lanark County, MPP for South Lanark, and a founder of multiple mills, helping drive the region’s economic growth.

- Walter Cameron, a blacksmith by trade, was also a gifted woodcarver and storyteller, his tales and craftsmanship making him a legend in his own time.

Through their contributions, Fallbrook flourished, carving out a distinct place in Ontario’s rich history.

Life was Not Easy for Mary Ann

After their marriage, John and Mary Ann Ashby settled on the 10th Line of Bathurst, near the mouth of Bennett Lake, just two and a half miles from Fallbrook. Their land, part of the Ashby family holdings, lay south of the lake and river, where they lived in a simple one-room log cabin built by an earlier generation of the Ashby family. It was sturdy but modest, nestled in the rugged beauty of the Ontario wilderness.

Mary Ann’s granddaughter later described her as “a very strong woman, both physically and mentally. A true pioneer, she stood shoulder to shoulder with her husband, helping my Great Grandpa build the one-and-a-half-story log house that still stands today”. But her contributions went far beyond her own home. She was a midwife and nurse to neighbors, a skilled gardener who grew an abundant supply of food, and a passionate reader who always had a book close at hand. Her hands were rarely idle—she could knit, crochet, and sew with expert precision, crafting items both practical and beautiful.

Their family grew quickly. In 1884, Mary Ann and John Ashby welcomed twins, Robert and Elizabeth, followed closely by William in 1885. John arrived in 1888, and Harriet in 1889. By 1891, when Isobella was born, the family was still living in their small, one-room cabin, with little space but plenty of love. Archie, the youngest, joined the family in 1893, adding to the lively household. Despite the challenges they faced, Mary Ann and John were building a home and family.

Life on the 10th Line of Bathurst was never easy, but, for John and Mary Ann Ashby, the years 1893 and 1900 brought sorrow beyond measure.

On February 12, 1893, Mary Ann gave birth to Archie, her youngest child at that time. Barely a month later, on March 10, her world was shattered when four-year-old Harriet fell ill suddenly and died within hours. Six days later, on March 16, the disease struck again. Ruth, aged nine, and John, aged five, were both lost in rapid succession, their young lives stolen by the ruthless grip of diphtheria. Diphtheria, spread through tiny droplets in the air, was merciless, attacking the throat and forming a thick, gray-black membrane that could choke the breath from a child in minutes. The odds were cruel. Desperate to protect her surviving children, Mary Ann strung a patchwork quilt soaked in carbolic acid across the cabin, a makeshift barrier against the invisible killer.Years later, in The Blacksmith of Fallbrook (1979), Walter Cameron recalled the heartbreak:

“John Ashby on the Tenth Line—I think he buried three children with scarlet fever or diphtheria, one of those contagious fevers, anyway. And nobody’d go near them, the fever spread so fast. So he’d make a box and take it down and bury a child in the graveyard, and then when he’d get back there’d be another one ready to go. Imagine that! And then one day his wife was carrying water up from the lake, putting it into a tub to wash, and while she was down getting a couple of pailfuls, a little boy (sic) drowned in the tub. Oh, they were the hard times!”

Tragedy struck again in 1900

Their youngest daughter, Charlotte, just 13 months old, wandered outside for only a few moments while her mother carried water from the lake. When Mary Ann found her, it was too late—she had drowned in a firkin of water by the door. The Lanark Era reported:

“The home of Mr. and Mrs. John Ashby, of Bathurst (near Fallbrook), was plunged into sorrow on Monday by the death by drowning of their thirteen-month-old daughter. The little one had been out of its parents’ sight scarcely three minutes, but during that time had fallen into a firkin1 of water outside the door, and when discovered, life was extinct. More than their share of trouble has fallen to the lot of Mr. and Mrs. Ashby, as only about four years ago three of their little ones were taken away in a brief period by diphtheria.”

Small, hand-carved stones now mark the graves of the three children lost in 1893, but it seems no stone was ever placed for John and Mary Ann themselves. Their son Robert, who had lost his twin sister Elizabeth, never married—perhaps forever haunted by those painful memories. And my grandmother, Isobella, the sixth child, suddenly found herself as the third surviving child and eldest daughter, her childhood forever changed by loss.

Life Goes On

Other children followed, joining Robert, William, Bella and Archie, the surviving children. Russell and Sarah, twins in 1895, Margaret in 1897, and Charlotte, the youngest, who was born in 1899 and died in 1900. Margaret died in 1925 of pulmonary tuberculosis.Life was hard. A new story and a half house of logs replaced the earlier single room cabin. A large garden was maintained, and babies birthed throughout the community. In addition to family duties, Mary Ann was a midwife for the community. Her daughters received only a basic education and went to work for local families, first assisting with childcare, later assuming the role of domestic help in the homes of families with more resources.

Mary Ann in Later Life

One of my favorite ‘finds’ about Mary Ann’s life came from a social column in the Lanark Era in 1910.

“Mrs. Wm. McCaw (Margaret Jane) and Miss Clark (Rachel) of Brockville, Mrs. John Ashby (Mary Ann) of the 11th (sic) line of Bathurst, and Mrs. Geo, Cavanagh (Marie Emily) of Frankville, the latter accompanied by her husband and two children, spent Sunday and Thanksgiving Day with their sister, Mrs. Wm. F. Heffron (Martha). It is twenty-six years since these five sisters met together, and on Monday they visited photographer Stead and had a group picture taken.

Although there may have been some strained relationships in the family, I believe that Mary Ann had few opportunities to travel. Her home and family were the focus of her life. Martha, who lived a short distance away was probably in touch from time to time but the others lived at a greater distance. Rachel, an older sister, would die the following year and may have been in poor health at this time. In 1910 Mary Ann and her four sisters met together for the first time in 26 years and arranged for a photo to be taken. I wonder if any of the descendants have preserved a copy of that photo?

In 1923, her son William, a survivor of injuries during World War I, passed away. In 1925 her daughter Margaret died of pulmonary tuberculosis. In 1926 Mary Ann was left a widow but continued to live in the log home that she and John built – a house that continues to be a home today.

As the years went by and her health failed, Mary Ann went to live with John and Bella Mather, my grandparents, who lived just a few miles from the Ashby home. Mary Ann passed away in the Great War Memorial Hospital in Perth, Lanark County, ON in 1941 at the age of 82.

“Mrs John Ashby

There passed away in the Great War Memorial Hospital, Perth, on Wednesday morning, February 26, Mary Ann Clark, widow of the late John Ashby of Fallbrook. Deceased was an esteemed resident of the community of Fallbrook, where she was well and favorably known.

The late Mrs. Ashby was in her 83rd year. She was born in Brockville, a daughter of the late James Clark and Mary A. Gillespie.

In 1883 she was united in marriage with John Ashby of Fallbrook, who predeceased her in 1926.Deceased was the mother of twelve children, four of whom died in early childhood. A daughter, Margaret, predeceased her in 1926; also a son, William, a Great War veteran, in 1923. Surviving members are: Robert on the homestead; Archie and Russel, in Alberta; Mrs John Lake, Glen Tay; Mrs. D.C. Nichols, Carleton Place, and Mrs. John Mather of Balderson, with whom the deceased lived after her health began to fail and she needed extra attention. Surviving also are one sister, Mrs. George Cavanagh of Vancouver; twenty-six grandchildren and nineteen great grandchildren.

Mrs. Ashby was a member of St Peter’s Anglican church at Fallbrook.

The funeral which was largely attended, was held Friday, at 10:30, from the home of her daughter, Mrs. John Mather, Balderson, assisted by Rev. Mr Dickinson of the Balderson United Church. The pallbearers were three grandsons, Harry Mather, Lyle Nichols, Beverley Nichols, and three nephews, Arden Lake, Delbert Lake and John Ashby.

The funeral tributes were very beautiful, and many expressions of sympathy were received by the bereaved family.

The Perth Courier

Perth, Ontario, Canada

March 6, 1941, pg. 3

Born of Irish parents who fled Northern Ireland, only to leave their relatives in the United States to start again in Canada, Mary Ann knew hardship from early childhood. Later, married and raising a family in a settler cabin, she experienced losses that a mother should never have had to bear. Possessing life sustaining skills, a strong spiritual belief, and a will to survive to the face of hardship, she provided for her family and assisted neighbours when she could. Her strong work ethic and household skills helped to sustain her daughters through many trials of their own.

Footnotes

- a firkin is a small wooden barrel or cask, traditionally used for storing liquids like water, ale, or butter. It typically holds about nine gallons (34 liters). In the tragic story of little Charlotte, the firkin of water outside the Ashby home was likely a large wooden bucket or tub, commonly used for household water storage in pioneer homes. [↩]